At age 22, aerospace mastermind Eric Shaw worked on some of the world’s most important aeroplanes, yet literacy to fly indeed the lowest bone was out of reach. Just out of council, he could n't go mercenary flight academy and spent the coming two times saving $12,000 to earn his private airman’s license. Shaw knew there had to be a better, less precious way to train aviators.

Now a graduate pupil at the MIT Sloan School of Management’s Leaders for Global Operations( LGO) program, Shaw joined the MIT Department of Aeronautics and Astronautics’( AeroAstro) Certificate in Aerospace Innovation program to turn a times-long reflection into a feasible result. Along with fellow graduate scholars Gretel Gonzalez and Shaan Jagani, Shaw proposed training aspiring aviators on electric and cold-blooded aeroplanes. This approach reduces flight academy charges by over to 34 percent while shrinking the assiduity’s carbon footmark.

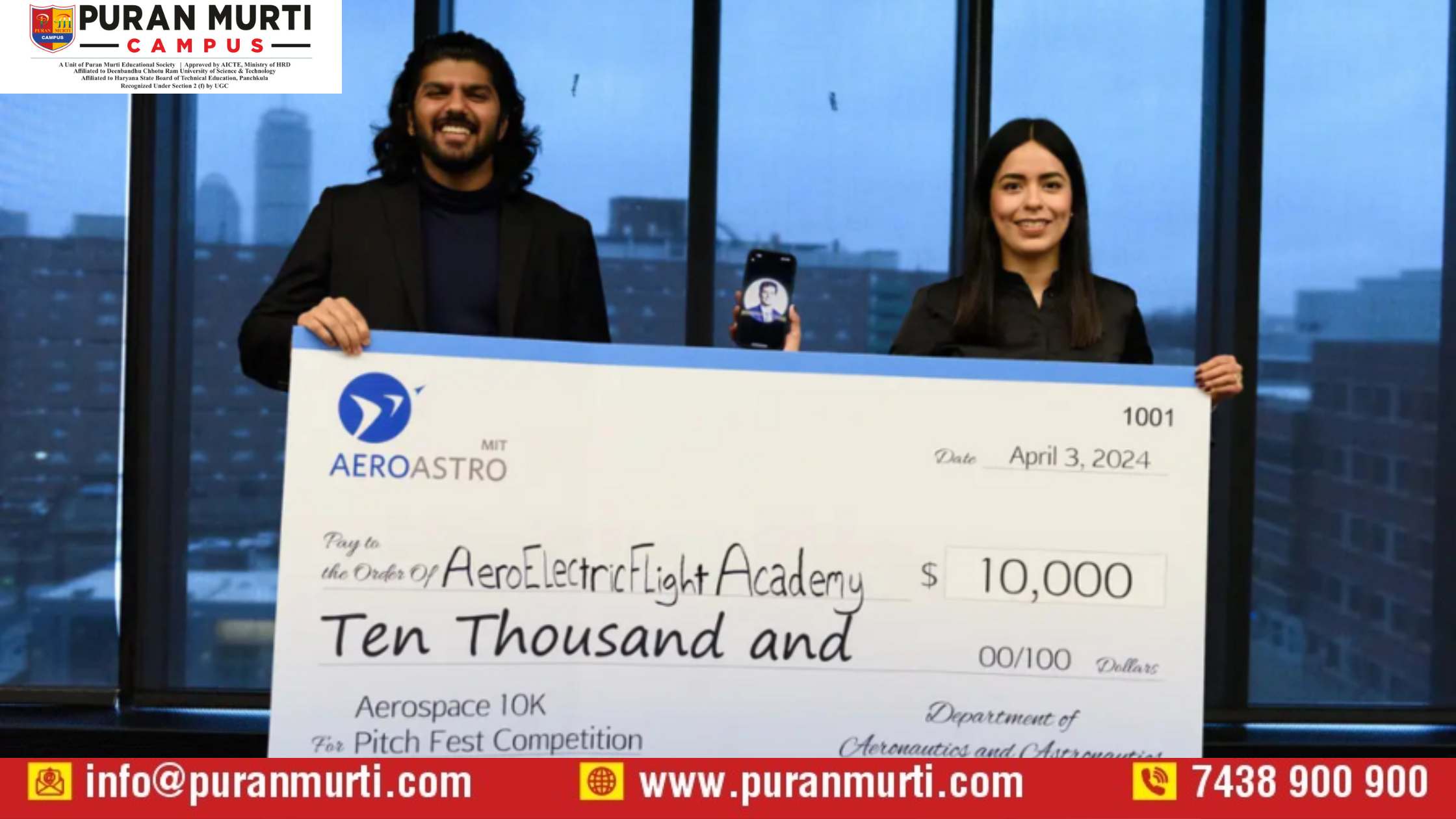

The triad participated their plan to produce the Aeroelectric Flight Academy at the instrument program’s hand Pitchfest event last spring. Equipped with a pitch sundeck and a business plan, the platoon impressed the judges, who awarded them the competition’s top prize of $10,000.

What began as a curiosity to test an idea has reshaped Shaw’s view of his assiduity.“ Aerospace and entrepreneurship originally sounded contrary to me, ” Shaw says. “ It’s a hard sector to break into because the capital charges are huge and a many big tykes have a lot of influence. Earning this instrument and talking face- to- face with folks who have overcome this putatively insolvable gap has filled me with confidence.”

dislocation by design

AeroAstro introduced the Certificate in Aerospace Innovation in 2021 after engaging in a strategic planning process to take full advantage of the exploration and ideas coming out of the department. The action is commanded by AeroAstro professors Olivier L. de Weck SM ʼ99, PhD ʼ01 and Zoltán S. Spakovszky SM ʼ99, PhD ʼ00, in cooperation with the Martin Trust Center for MIT Entrepreneurship. Its creation recognizes the aerospace assiduity is at an curve point. Major advancements by drone, satellite, and other technologies, coupled with an infusion of nongovernmental backing, have made it easier than ever to bring aerospace inventions to the business.

“The geography has radically shifted, ” says Spakovszky, the Institute’s T. Wilson( 1953) Professor in Aeronautics.“ MIT scholars are responding to this change because startups are frequently the quickest path to impact ”

The instrument program has three conditions coursework in both aerospace engineering and entrepreneurship, a speaker series primarily featuring MIT alumni and faculty, and hands- on entrepreneurship experience. In the ultimate, actors can enroll in the Trust Center’s StartMIT program and also contend in Pitchfest, which is modeled after the MIT $100K Entrepreneurship Competition. They can also join a summer incubator, similar as the Trust Center’s MIT delta v or the Venture Exploration Program, run by the MIT Office of Innovation and the National Science Foundation’s Innovation Corps.

“At the end of the program, scholars will be suitable to look at a specialized offer and fairly snappily run some figures and figure out if this invention has request viability or if it’s fully romantic, ” says de Weck, the Apollo Program Professor of Astronautics and associate department head of AeroAstro.

Since its commencement, 46 people from the MIT community have shared and 13 have fulfilled the conditions of the two- time program to earn the instrument. The program’s fourth cohort is underway this fall with its largest registration yet, with 21 postdocs, graduate scholars, and undergraduate seniors across seven courses and programs at MIT.

A unicorn assiduity

When Eddie Obropta SM ʼ13, SM ʼ15 attended MIT, aerospace entrepreneurship meant working for SpaceX or Blue Origin. Yet he knew more was possible. He gave himself a crash course in entrepreneurship by contending in the MIT $100K Entrepreneurship Competition four times. Each time, his ideas came more refined and battle- tested by implicit guests.

In his final entry in the competition, Obropta, along with MIT doctoral pupil Nikhil Vadhavkar and Forrest Meyen SM’13 PhD’ 17, proposed using drones to maximize crop yields. Their business, Raptor Charts, won. moment, Obropta serves as theco-founder and principal technology officer of Raptor Charts, which builds software to automate the operations and conservation of solar granges using drones, robots, and artificial intelligence

While Obropta entered support from AeroAstro and MIT's being entrepreneurial ecosystem, the tech leader was agitated when de Weck and Spakovszky participated their plans to launch the Certificate in Aerospace Innovation. Obropta presently serves on the program’s premonitory board, has been a presenter at the speaker series, and has served as a tutor and judge for Pitchfest.

“While there are a lot of excellent entrepreneurship programs across the Institute, the aerospace assiduity is its own unique beast, ” Obropta says. “ moment’s aspiring authors are visionaries looking to make a spacefaring civilization, but they need technical support in navigating complex multidisciplinary operations and heavy government involvement. ”

Entrepreneurs are far and wide, not just at startups

While the instrument program will probably produce success stories like Raptor Charts, that is n't the ultimate thing, say de Weck and Spakovszky. Allowing and acting like an entrepreneur — similar as understanding request eventuality, dealing with failure, and erecting a deep professional network — are characteristics that profit everyone, no matter their occupation.

Paul Cheek, administrative director of the Trust Center who also teaches a course in the instrument program, agrees.

“At its core, entrepreneurship is a mindset and a skill set; it’s about moving the needle forward for maximum impact, ”Cheek says. “A lot of associations, including large pots, nonprofits, and the government, can profit from that type of thinking.”

That form of entrepreneurship resonates with the Aeroelectric Flight Academy platoon. Although they're meeting with implicit investors and looking to gauge their business, all three plan to pursue their first heartstrings Jagani hopes to be an astronaut, Shaw would like to be an superintendent at one of the “ big canine ” aerospace companies, and Gonzalez wants to work for the Mexican Space Agency.

Gonzalez, who's on track to earn her instrument in 2025, says she's especially thankful for the people she met through the program.

“I didn’t know an aerospace entrepreneurship community indeed was when I began the program, ” Gonzalez says. “ It’s then and it’s filled with veritably devoted and generous people who have participated perceptivity with me that I do n’t suppose I would have learned anywhere differently. ”